Since the 9 November 2021 ceasefire agreement between Azerbaijan and Armenia that ended the 44 day-long war between the two over Nagorno-Karabakh and the surrounding regions, Armenia has been going through difficult times. This is not an unexpected aftermath of the 2020 Karabakh War for it resulted by the defeat of Armenia. The disillusionment of the Armenians and the subsequent situation in Armenia is by no means a surprise. Similar disorders could be experienced in any country that has suffered defeat in war. Yet, the myths that the Armenian political, military and cultural elite had created for years, such as the invincibility of the Armenian army and the solidarity of its allies, might have intensified frustration, confusion, and helplessness felt by the Armenians.

One of the expected developments in the aftermath of the 2020 Karabakh War was the upsurge of criticisms targeting the Pashinyan government for loss of the war. This has, indeed, happened; since the signing of the ceasefire agreement, Pashinyan and his ruling party have been facing serious accusations coming from different sections of the Armenian society. Anti-Pashinyan protests have been going on since then. In December, an opposition movement was formed with the name “Homeland Salvation Movement” (HSM) as the coalition of seventeen oppositional parties and groups. Yet, in the last two weeks, the situation in Armenia has gotten more intense.

On 20 February, after a relatively crowded street protest, the HSM declared that it would hold continuous protests until its demands are met. On 23 February, protesters attempted to prevent Pashinyan from entering the government building and some protesters were detained by the police. The real blow, however, came on 25 February, when over forty military officers including the Chief of General Staff Onik Gasparyan, issued a statement demanding Pashinyan’s resignation. To underpin their demand, signatories of the statement accused Pashinyan of bringing Armenia to the “to the brink of collapse” and “no longer” being “able to make adequate decisions.” As a response, Pashinyan called his supporters to the streets and condemned the statement as an “an attempted coup” in his address to approximately 20,000 people that gathered to support him. On the same day, Pashinyan dismissed Gasparyan from his post. This was the second dismissal of a top military officer. On 24 February, Pashinyan dismissed the First Deputy Chief of the General Staff Tiran Khachatryan after the latter ridiculed Pashinyan for his statement about the Russian made Iskender missiles a day before. However, President Armen Sarkissian refused to sign Gasparyan’s dismissal on 27 February and for the second time on 2 March arguing that the dismissal of the Chief of General Staff was unconstitutional.

As can be seen, the recent political crisis in Armenia has multiple actors; Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and his My Step alliance, the opposition composed of different political entities and figures, high ranking military officers including the Chief of General Staff, and President A. Sarkissian. Since the ways in which the current crisis in Armenia would unfold may have repercussions that reach beyond Armenia itself and affect the post-2020 Karabakh War situation in the South Caucasus, this complicated situation needs utmost attention.

When we look at the opposition we see mostly the ‘old elite,’ including former presidents Robert Kocharyan and Serzh Sargsyan, the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), businessman and the leader of the Prosperous Armenia Party Gagik Tsarukyan and others. One noteworthy figure that deserves mentioning is Artur Vanetsyan, the former Head of the National Security Service and the leader of the newly formed Homeland Party.

Kocharyan and Sargsyan, with active role in the First Karabakh War, belong to the same political tradition. Kocharyan had been the President of the country between 1998 and 2008. He was succeeded by Sargsyan between 2008 and 2018 until he was ousted by the Pashinyan-led ‘Velvet Revolution’ in April-May 2018. It is not a secret that there is a political blood feud between these two and Pashinyan. Similar feuds exist between Pashinyan and the other oppositional actors. As to that, the row between Pashinyan and Artur Vanetsyan might deserve particular emphasis.

Among a number of ‘old elite,’ the front man of the HSM, hence much of the opposition, is Vazgen Manukyan. Manukyan is also a figure from the 1990s and the First Karabakh War like Kocharyan and Sargsyan. He served as the Prime Minister between 1990 and 1991 and as the Minister of Defense between 1992 and 1993. He had been a deputy between 1995 and 2007. In 1996, he ran for the presidency against Levon Ter-Petrosyan, the first president of Armenia between 1991 and 1998, but lost with 41% of the votes against 52% that Ter-Petrosyan received. He also ran in the elections in 1998, 2003, and 2008, gaining 13%, 1%, and 1.3%, respectively. As these figures reveal, Manukyan, until recently, was a long-gone political figure. Only few months ago did he make a return to the political scene. Apparently, the fact that he is perceived as one of the architects of the Armenian victory in the First Karabakh War has enabled his recent comeback to politics following Armenia’s defeat in the Second Karabakh War.

For the time being, opposition does not look strong enough vis-à-vis Pashinyan. One of the weaknesses of the opposition –hence the strength of Pashinyan- is the disunity of the opposition in their demands. Whereas a group led by Manukyan demands Pashinyan’s resignation and the formation of an interim government by Manukyan to bring the country to snap elections, others do not insist on Pashinyan’s resignation and only stress the need for snap elections. In fact, Pashinyan has already declared that he will not resign, but also that he does not oppose snap elections. In this sense, Pashinyan and some elements of the opposition are on the same track.

Another weakness of the opposition is their lack of unified or separately formulated sound policy proposals to end the crisis in the country. Except for the rhetoric of the unacceptability of ‘Armenia’s capitulation to Azerbaijan’ by the signing of the 9 November 2020 ceasefire agreement, they suggest no perspective on Armenia’s self-inflicted defeat and a sound recipe for a way out from the current situation. To make for this gap, a radical, revanchist and adventurist rhetoric is being used, which is coupled with accusations against Pashinyan for being a traitor. The opposition also does not refrain from racist insults such as calling Pashinyan a “Turkish spy” or just a “Turk” (implying that being a Turk is considered an insult by itself). In brief, the opposition gets together only on an anti-Pashinyan agenda without any positive policy outline.

The fact that some of the opposition demands resignation of Pashinyan before the snap elections is a revelation of another of its weaknesses. This weakness is that although there is a significant level of discontent with Pashinyan, there is a bigger discontent with, or event disgust of the old elite. Put differently, although Pashinyan’s heydays have long been over, he is still more preferable than his opponents; in the eyes of the majority of the Armenians, Pashinyan is bad, but the old elite is worse. The relative strength of Pashinyan vis-à-vis his rivals can be seen from the masses that fill the streets to support either him or the opposition. Observers point out that opposition rallies do not gather significantly large crowds. They also argue that opposition rallies are mostly attended by a rather homogeneous group mostly composed of older males. On the contrary, Pashinyan supporters seem to come from diverse social backgrounds, pointing that he still has support from different sections of the society. In brief, Pashinyan still seems to be relatively strong and is likely to win the snap elections. At least, electoral victory is not guaranteed for the opposition.

The relative weakness of the opposition coupled with its radical rhetoric signals a risk. This risk is the possibility of the opposition’s possible inclination towards resorting to undemocratic ways to seize power. As to this, it is striking that in public rallies Manukyan does not hesitate to preach seizing power by force. For example on 20 February, he called upon the members of the HSM to be “ready for the uprising” and said “you have to be ready to take power at any moment by rebellion with a lightning speed.” Besides this sort of provocative statements, he also called upon the police and the national security service to join the army against Pashinyan, perhaps taking courage from President Sarkissian’s refusal to sign the decrees about the dismissal of the Chief of General Staff.

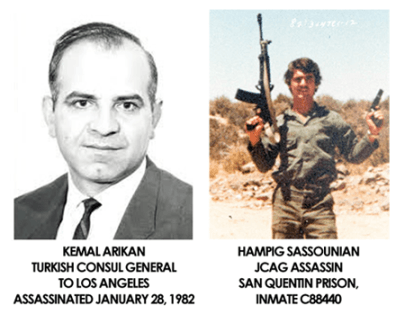

To properly assess the risks in Armenia, one should recall the thirty year-long history of the Republic of Armenia that has many instances of political violence. For example, in the aftermath of the 1996 elections, some 150-200 thousand Manukyan supporters attempted to invalidate the election results by force. During the infamous 1999 parliamentary shooting five terrorists killed eight deputies including the Prime Minister Vazgen Sargsyan and Parliament Speaker Karen Demirchyan. Importantly, this incident marked the death of a very probable peace deal negotiated by the then presidents of Azerbaijan and Armenia based on the exchange of territories. After the 2008 presidential elections chaos ruled the streets, which left around ten people dead. Lastly, in July 2016 a group of armed men raided a police station in Yerevan and took the policemen hostage for about two weeks. They demanded the release of a ‘Karabakh war hero’ named Jirair Sefilian to be released from prison and the then President Serzh Sargsyan to resign. The toll of this event was three dead policemen and hundreds of wounded during clashes between the supporters of the terrorist group and the police. Given the history of political violence of Armenia, the confrontation between the opposition and Pashinyan can be deemed as alarming. The participation of the ARF, the repertoire of which includes terrorism not only against the Turks and the Azerbaijanis but also against the Armenians, in the opposition camp and the declaration published on 20 January in the name of the Armenian terrorist organization ASALA in a Prague-based journal that threatened Turkey, Azerbaijan and the Armenian officials for the defeat, may turn up the alarm bell.

On a positive note, on the other hand, opportunely, until now there have been no clashes between the supporters of the opposition and Pashinyan who rally in the streets of Yerevan at the same times save for several fistfights. Some Armenian observers argue that there is no significant level of tension in the society. Despite that, it is hard to guarantee that there would not be any armed incidents or provocations to pull the security forces in or to create an excuse for that. After all, the aforementioned 1999 parliamentary shooting were carried out by only five gunmen and the 2016 police station raid, known as the 2016 Hostage Crisis, by few dozen militants. As to this, attention should also be paid to Pashinyan’s public speech on 25 February, at which he said “the velvet is over,” possibly implying that he would resort to more aggressive stance against his rivals. If the escalation continues in Armenia, we may witness developments uglier than fistfights.

* Photo: JAM news

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

PASHINYAN CALLS ON ARMENIAN DIASPORA TO BEHAVE RESPONSIBLY

PASHINYAN CALLS ON ARMENIAN DIASPORA TO BEHAVE RESPONSIBLY

PROTESTS AGAINST THE “SOCIAL PARASITE TAX” IN BELARUS

PROTESTS AGAINST THE “SOCIAL PARASITE TAX” IN BELARUS

THE NEW KID ON THE BLOCK: LATVIAN PARLIAMENT’S RECOGNITION OF THE ‘ARMENIAN GENOCIDE’

THE NEW KID ON THE BLOCK: LATVIAN PARLIAMENT’S RECOGNITION OF THE ‘ARMENIAN GENOCIDE’

DEVELOPMENTS IN POST-2020 KARABAKH WAR ARMENIA AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS - III: PRESIDENT A. SARKISSIAN: A WISE MAN OR AN OPPORTUNIST?

DEVELOPMENTS IN POST-2020 KARABAKH WAR ARMENIA AND THEIR IMPLICATIONS - III: PRESIDENT A. SARKISSIAN: A WISE MAN OR AN OPPORTUNIST?

THE ‘ARMENIAN QUESTION’ IN UKRAINE - I: A POTENTIAL PROBLEM IN A PROMISING RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TURKEY AND UKRAINE

THE ‘ARMENIAN QUESTION’ IN UKRAINE - I: A POTENTIAL PROBLEM IN A PROMISING RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TURKEY AND UKRAINE

BIASED COVERAGE OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE IN WWI AND THE 1915 EVENTS

BIASED COVERAGE OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE IN WWI AND THE 1915 EVENTS

A HYPOCRITICAL CALL FOR INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE

A HYPOCRITICAL CALL FOR INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE

WILL THE U.S. STATE OF CALIFORNIA GIVE GREEN LIGHT TO TERRORISM?

WILL THE U.S. STATE OF CALIFORNIA GIVE GREEN LIGHT TO TERRORISM?

UNDER WESTERN PRESSURE, KOSOVO VOTES IN FAVOR OF THE CREATION OF WAR CRIMES COURT

UNDER WESTERN PRESSURE, KOSOVO VOTES IN FAVOR OF THE CREATION OF WAR CRIMES COURT

AN OVERVIEW OF THE YEAR 2024

AN OVERVIEW OF THE YEAR 2024