From “reset” language to legal constraints

Recent discussions of a supposed “reset in the Black Sea” have tended to frame the region as an arena where renewed French–Turkish convergence could engineer a fresh strategic balance, implicitly suggesting that political will and minilateral formats might override existing constraints. In this narrative, the Black Sea appears as an almost vacant stage on which external actors can experiment with new security roles and burden-sharing arrangements. This commentary instead approaches the issue from the perspective of law and institutional practice, arguing that the Black Sea constitutes a legally framed regional security space whose core parameters are defined by the Montreux Convention and by littoral responsibility, rather than by ad hoc strategic projects.[1]

Montreux, littoral responsibility, and regional cooperation

The 1936 Montreux Convention established a special regime for the Turkish Straits that combines freedom of passage for merchant vessels with far-reaching rights and responsibilities for Türkiye over naval access to and from the Black Sea. In both peace and war, it is Türkiye that supervises and implements these rules, including the power to restrict or close the Straits under defined conditions, which grounds its gatekeeping role legally and makes it non-delegable. As such, the Black Sea Economic Cooperation framework was conceived in 1992 as a primarily economic and functional mechanism among littoral and neighboring states, aiming at trade, connectivity, and prosperity rather than externalized security governance.[2]

Misplaced expectations about shared gatekeeping

Building on this treaty-based framework, it is to be underscores that Türkiye neither needs nor is legally required to “share” the implementation of the Straits regime with any other state, whether an individual EU member state or a broader coalition. The Convention vests authority and responsibility for naval access exclusively in Ankara, so proposals for joint gatekeeping remain political constructs rather than credible legal options. The “reset” narrative advanced in recent discussions implicitly normalizes the idea that new bilateral or minilateral formats could recalibrate Montreux's practice without openly addressing treaty revision, thereby blurring the line between diplomacy and legal engineering. Treating Turkish control as an adjustable variable in this way risks eroding legal predictability and incentivizing selective compliance by other actors in future crises.[3]

Eurocentric shortcuts and regional marginalization

Building on these legal and institutional premises, it is important to situate contemporary “reset” narratives within the longer trajectory of EU and NATO approaches to the Black Sea. Over several decades, European and Euro‑Atlantic strategies have tended to channel their regional engagement primarily through the accession and subsequent integration of Romania and Bulgaria, as well as through various sectoral initiatives, while often only nominally acknowledging Türkiye as a core stakeholder. In this discourse, European actors frequently cast themselves as principal architects of regional order, with Türkiye implicitly positioned as an implementer or facilitator rather than as a primary coastal power with its own security culture and historical memory. The current “reset” language risks reproducing this hierarchy, which sits uneasily with a more balanced regional outlook that resists one-sided victimhood narratives and insists on comparative, multi-layered readings of conflicts and legal claims across different theatres.[4]

Cooperation without dilution

Against this background, the normative benchmark that emerges is not one of isolation but of principled openness. A coherent approach would insist, first, on strict fidelity to the Montreux provisions and on the primacy of littoral states in shaping Black Sea security arrangements, thereby preserving the clarity of existing legal responsibilities. At the same time, it would welcome pragmatic cooperation with France and other European actors in areas such as trade, connectivity, energy infrastructure, and confidence-building measures, provided these initiatives do not seek to re-engineer the Straits regime by stealth. European proposals should therefore align themselves with, rather than “upgrade,” established frameworks: respecting tonnage and passage rules, reinforcing inclusive regional formats, and avoiding language that implies any form of shared or delegated control over access to the Black Sea.

Preserving legal order, avoiding conceptual inflation

Taken together, these considerations suggest that any durable re-framing of Black Sea politics must begin with an unambiguous recognition of Türkiye’s treaty-based responsibilities and of the institutional landscape already binding the region, rather than with politically convenient shortcuts or informal reinterpretations. A “reset” that rests on loosely defined strategic narratives or treats established regimes as flexible instruments of day-to-day diplomacy risks eroding both legal concepts and confidence among coastal states. By contrast, a law-conscious, region-centered approach that respects existing obligations while encouraging calibrated cooperation offers a more credible and sustainable path for future European–Turkish engagement in the Black Sea.[5]

*Picture: Carnegie Endowment

[1] Romain Le Quiniou, “France, Turkey, and a Reset in the Black Sea,” Carnegie Europe, January 13, 2026, accessed February 4, 2026, https://carnegieendowment.org/europe/strategic-europe/2026/01/france-turkey-and-a-reset-in-the-black-sea?lang=en

[2] Teoman Ertuğrul Tulun, “Constructive Eurasianism and Cooperative Security: AVİM’s Perspective on the Black Sea Region,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), commentary, October 10, 2025, accessed February 4, 2026, https://avim.org.tr/en/Yorum/CONSTRUCTIVE-EURASIANISM-AND-COOPERATIVE-SECURITY-AVIM-S-PERSPECTIVE-ON-THE-BLACK-SEA-REGION ; Alev Kılıç , “Cooperation at the Wider Black Sea Basin and Changing Times – I,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), commentary, October 27, 2025, accessed February 4, 2026, https://avim.org.tr/en/Yorum/COOPERATION-AT-THE-WIDER-BLACK-SEA-BASIN-AND-CHANGING-TIMES-1.

[3] Teoman Ertuğrul Tulun, “Guardianship in Practice: Leadership, Adaptation, and Security Challenges in the Black Sea,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), analysis, October 16, 2025, accessed February 4, 2026, https://avim.org.tr/en/Analiz/GUARDIANSHIP-IN-PRACTICE-LEADERSHIP-ADAPTATION-AND-SECURITY-CHALLENGES-IN-THE-BLACK-SEA

[4] Teoman Ertuğrul Tulun, “At the Crossroads: Türkiye and the Battle for Black Sea Order,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), analysis, October 21, 2025, accessed February 4, 2026, https://avim.org.tr/en/Analiz/AT-THE-CROSSROADS-TURKIYE-AND-THE-BATTLE-FOR-BLACK-SEA-ORDER

[5] Teoman Ertuğrul Tulun, “Guardianship Of Meaning: Russian Disinformation, European ‘Gospels Of Hate,’ And Türkiye’s Legal Stability In The Black Sea,” Eurasian Security Bulletin (EurasiaSec), analysis, January 12, 2026, accessed February 4, 2026, https://www.eurasiasec.org/guardianship-of-meaning ; Teoman Ertuğrul Tulun, “Constructive Eurasianism and Past Reflections,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), commentary, September 22, 2025, accessed February 4, 2026, https://avim.org.tr/en/Yorum/CONSTRUCTIVE-EURASIANISM-AND-PAST-REFLECTIONS

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

CONSTRUCTIVE EURASIANISM AND PAST REFLECTIONS

CONSTRUCTIVE EURASIANISM AND PAST REFLECTIONS

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 22.09.2025 -

MUNICH SECURITY CONFERENCE 2026 DEBRIEF

MUNICH SECURITY CONFERENCE 2026 DEBRIEF

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 23.02.2026 -

THE AUTONOMOUS TERRITORIAL UNIT OF GAGAUZIA AND MOLDOVA'S EU CANDIDACY

THE AUTONOMOUS TERRITORIAL UNIT OF GAGAUZIA AND MOLDOVA'S EU CANDIDACY

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 30.10.2025 -

NSU CASE COVERED UP AND LEGALLY CLOSED: IS IT POSSIBLE TO AVOID SOCIAL AND POLITICAL REPERCUSSIONS?

NSU CASE COVERED UP AND LEGALLY CLOSED: IS IT POSSIBLE TO AVOID SOCIAL AND POLITICAL REPERCUSSIONS?

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 20.12.2021 -

FRANCE, TÜRKİYE, AND THE BLACK SEA ORDER: LEGAL REALITIES VERSUS STRATEGIC SHORTCUTTING

FRANCE, TÜRKİYE, AND THE BLACK SEA ORDER: LEGAL REALITIES VERSUS STRATEGIC SHORTCUTTING

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 04.02.2026

-

UZBEKISTAN SHOWS ITS MATURITY

UZBEKISTAN SHOWS ITS MATURITY

Ali Murat TAŞKENT 29.09.2016 -

2016 WARSAW SUMMIT AND THE NAGORNO KARABAKH ISSUE

2016 WARSAW SUMMIT AND THE NAGORNO KARABAKH ISSUE

Osman GÜN 14.07.2016 -

GEORGIA’S CONTRADICTORY POLICIES ENDANGER REGIONAL COOPERATION

GEORGIA’S CONTRADICTORY POLICIES ENDANGER REGIONAL COOPERATION

Aslan Yavuz ŞİR 07.02.2019 -

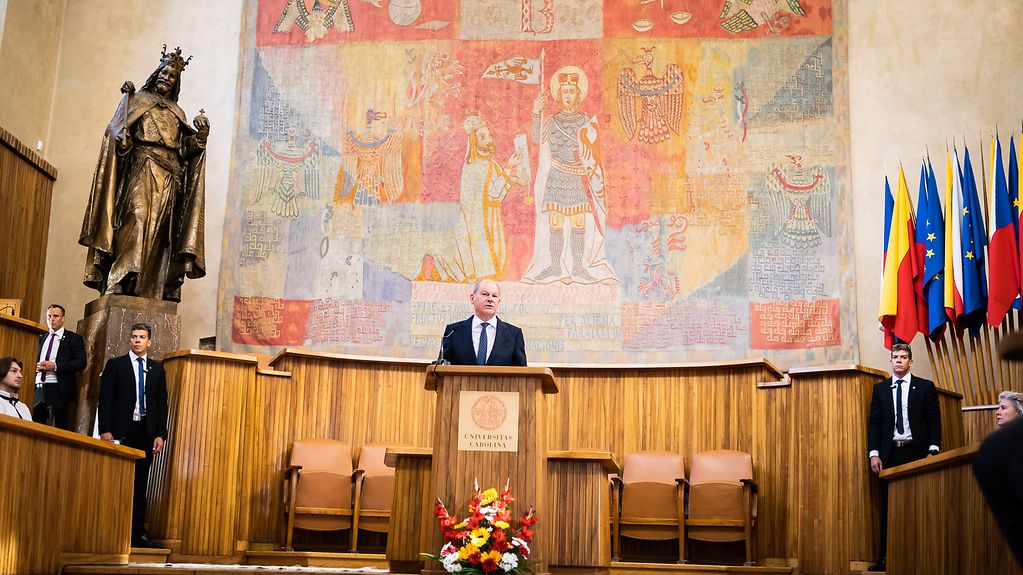

SCHOLZ'S DREAMS OF AN EU WITHOUT TURKEY

SCHOLZ'S DREAMS OF AN EU WITHOUT TURKEY

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 07.09.2022 -

THE DECISION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ON TURKEY’S ACCESSION PROCESS: ADVICE FOR WHAT PURPOSE?

THE DECISION OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ON TURKEY’S ACCESSION PROCESS: ADVICE FOR WHAT PURPOSE?

AVİM 13.07.2017

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"