Introduction

The term “theopolitics” was coined by the philosopher and professor of Judaism Martin Buber in his work “Kingship of God.”[1] Buber’s theopolitics stressed that “politics must be rendered theological, not theology rendered political.” Hence, he prioritized theology over politics. In other words, in his view, “all politics must be placed into the service of God.”[2]

Orthodox Christianity is often defined as the Eastern branch of Christianity that split from the West.[3] In the Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, the Orthodox Church is described as “a family of Churches, situated mainly in Eastern Europe: each member Church is independent in its internal administration, but all share the same faith and are in communion with one another, acknowledging the honorary primacy…”[4] of the İstanbul Fener Greek Orthodox Patriarchate (hereupon, “Patriarchate in İstanbul” ). Eastern Christianity has a polycentric structure. This is mainly the result of political changes. Especially the emergence or disappearance of centralized political authority of the state. In this period, Miaphysitism, which considered Jesus is fully divine and fully human in one nature or substance (physis), gained influence over Orthodox Christianity in Egypt-Alexandria, Antioch, and Armenian churches. The Armenian Church later adopted the Gregorian-Apostolic way to differ itself from the Byzantium practices. Academic resources draw attention to the fact that this division reflects the dissatisfaction with the domination of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, and it is mentioned that ethnocultural differences play a key role in the divisions within the church.[5] As per academic sources, Bulgaria is a prime example of these divisions and the existence of independent (autocephalous) Eastern Churches in the Balkans. After establishing independent Bulgaria, Bulgarians broke ecclesiastical ties with the Patriarchate in İstanbul and constituted their autocephalous Patriarchate. Three years after they lost their independence and were subjected to the Ottoman Empire in 1393, the Patriarchate was abolished and subordinated to Patriarchate in İstanbul. When the Sultan Abdulaziz of the Ottoman Empire restored the Bulgarian Church with his Ferman (edict) as an independent exarchate in 1870 against the will of the Patriarchate in İstanbul, it took 75 years until the Patriarchate in İstanbul recognized Bulgarian autocephaly in 1945.[6]

It should be noted that the Greek Orthodox church was declared autocephalous in 1833.[7] The unilateral declaration of autocephaly caused a protracted crisis between Greece and Patriarchate in İstanbul. The Patriarchate in İstanbul objected to unilateralism as a severe violation of the procedures stipulated by Orthodox canon law. As a result, the Church of Greece remained in a condition of schism, unrecognized by the Orthodox Churches until 1850, when the Patriarchate in İstanbul, following a formal application by the Greek government and the Synod of the Church of Greece, issued a patriarchal decision canonically granting autocephaly and readmitting Greece into the communion of Orthodox Churches.[8]

The second half of the 19th century witnessed the emergence of nation-states. Concurrently, the relationship between nationalism and religion emerged in Orthodoxy and the Patriarchate in İstanbul faced autonomy or autocephaly requests from the religious and political leaders of the newly formed Romania and Serbia. While the Patriarchate in İstanbul gradually recognized the autocephaly of churches in the new Balkan countries, it also denounced a situation where the identity of a local church was based solely on nationality, namely “ethnophiletism.”[9]

As per the Serbian Orthodox Church (SOC), in contrast to Greek unilateralism, the autonomous principality of Serbia faithfully followed the formalities of canon law and obtained smoothly from Patriarchate in İstanbul the status of autonomy of the Serbian Church in 1831. Accordingly, autocephaly came equally smoothly in 1879 because of the recognition of Serbian independence by the Congress of Berlin. Upon independence, the Serbian government applied to the Patriarchate in İstanbul and received the authorization of autocephaly.[10] Between 1879 and 1920, the Orthodox Serbian community was governed by at least six ecclesiastical jurisdictions (Carlowitz, Montenegro, Dalmatia and Cattaro, Belgrade, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Southern Serbia, the latter two dependent on Patriarchate in İstanbul). Serbia participated in the First World War on the side of the victors, which prepared the ground for the advent of the Yugoslav Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. The need for ecclesiastical integration led to another appeal in 1919 to Patriarchate in İstanbul whereby consent was requested to integrate the six jurisdictions into one united patriarchate of all Serbs. On 12 September 1920, the feast day of all Serbian saints, the unification of all jurisdictions into one Serbian Patriarchate was celebrated. On 2 April 1922, a mission from Patriarchate in İstanbul delivered the patriarchal authorization issued by Patriarch Meletios IV to the Patriarch of all Serbs Demetrie. Thus, ecclesiastical integration came into being, and patriarchal status evoked the unity of the Serbian religious community.

Ecclesiastical Battle of Montenegrins with the Serbian Orthodox Church

Montenegro became independent in 1878 by the decision of the Berlin Congress. A 40-year period of independence ended with Montenegro's unification with Serbia in 1918. It was later incorporated into the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes (which became the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in 1929). After the collapse of the Yugoslav state and the outbreak of war in 1941, it became a republic within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Following the collapse of that state in the early 1990s, Montenegro remained within former Yugoslavia, shortly known as the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, and then a looser federal structure called Serbia and Montenegro. In May 2006, an absolute majority of its citizens voted for independence.

This summary of the period until the foundation of modern Montenegro also briefly reflects the history of the Montenegrin Orthodox Church (MOC). As noted earlier, Montenegro was an independent state until the end of the First World War, and Orthodoxy was a state religion. In this regard, MOC was also the state church. In 1918, Montenegro was unified with the Kingdom of Serbia. Subsequently, in 1920, the MOC was incorporated into the United SOC of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes. This historical overview explains how the state and religion are intertwined in the Orthodox world, to what extent religion is an integral part of politics, and how deeply rooted the understanding of one state-one church is.

A national church in the Balkans has been central to forming national identity since Ottoman rule, and it remained an essential reference for national identity. We observe this phenomenon in Montenegro as well. In this sense, pro-independence Montenegrins argued that the MOC (which they believed had had its autonomy revoked illegally in 1920) should be re-established.[11] The MOC was founded in Cetinje on October 31, 1993, by Antonije Abramović, initially with the support of the Liberal Alliance of Montenegro (LSCG), a political party at the time. According to academic sources, the re-establishment of the Montenegrin Church in 1993 sought to redress this imbalance, an act the Serbian Church perceived as controversial, provocative, ultimately illegal, and primarily political. Pro-independence Montenegrins re-established the autocephalous MOC in the hope that it would facilitate the unification of all Montenegrins through the worship of specifically Montenegrin saints and cults – a vital stage in consolidating and reinforcing Montenegrin national identity. They hoped this would aid the medium-term objective of establishing an independent Montenegrin state, with the church acting as the central pillar of the nation.[12] It should be noted that the MOC, in the orthodox canonical sense, de jure, is not recognized either by the SOC or the Patriarchate in İstanbul. In this context, it is helpful to remember the following statement made by Patriarch Bartholomew at the end of 2019:

“The Patriarchate of [İstanbul] will always stand with its Serbian brothers and sisters and will never give autocephaly to the schismatic Montenegrin Orthodox Church… The Church in Montenegro is the Serbian Orthodox Church, and there will never be any changes … I told President Milo Đukanović about this. The only canonical Church in Montenegro is the Montenegrin-Primorye Metropolis of the Serbian Orthodox Church, and the only canonical Archbishop is Metropolitan Amfilohije… I fully support Metropolitan Amfilohije, at whose request I wrote a letter to the President of Montenegro Milo Đukanović, in which I urged him not to take further steps in the adoption and implementation of laws on religious communities:”[13]

Agreement Signed with the SOC Leads to the Fall of the Montenegrin Government: The Power of Theopolitics

As per press reports, the Montenegrin government fell in a no-confidence vote on 20 August 2022 that followed a rift over relations with the powerful SOC. Lawmakers voted 50-1 to oust the government of Prime Minister Dritan Abazovic just weeks after he signed an agreement regulating the position of the Serbian church in Montenegro.[14] The mentioned reports draw attention to the point that “the Serbian Orthodox Church enjoys the biggest following in Montenegro, but the nation is divided over the church’s dominant role and the country’s ties to Serbia.” The reports argued that “there was no need for a special deal with the Serbian church separate from other religious communities, and the pro-Western groups in Montenegro have described the agreement as a tool for Serbia and Russia to increase their influence in Montenegro amid the war in Ukraine.” It is mentioned in the reports that reaching an agreement with the SOC has proved highly politically sensitive, despite the fact that SOC is the largest religious organization in Montenegro, with the majority of the Orthodox population, whether they define themselves as Serb or Montenegrin, as followers. Nevertheless, many Montenegrins of Orthodox faith belonging to the MOC regard the SOC as an instrument of Serb nationalism and its followers as proponents of the “Serbian World” which actively engaged in undermining Montenegro’s statehood and statehood the identity of Montenegrins.[15]

Conclusion

The historical development of the Orthodox Church in the Balkans, its strong role in the internal/international politics of the countries and formation of the national identity, and its dominance in the state structures are unique examples of explaining the concept of theapolitics. Parallel to the formation of national identity, the fact that religious identity dominates and directs the rulers and leaders of the state comes to light as one of the main features of orthodoxy. The intertwining of state and religion inevitably makes orthodoxy the state religion, especially in the Balkans. A prominent example of this is Greece. In this context, secularism, one of the essential basic concepts of the modern state, loses its importance in this kind of bigotry, becomes a dominant character of national identity, and can be pushed into the background. In this context, Greece is the best example we come across in the Balkans. In Greece, which is claimed to be the cradle of democracy, the Constitution depicts Greek Orthodoxy as the state religion. The third article of the Greek Constitution reads as follows:

“SECTION II. Relations of Church and State

Article 3

1. The prevailing religion in Greece is that of the Eastern Orthodox Church of Christ. The Orthodox Church of Greece, acknowledging our Lord Jesus Christ as its head, is inseparably united in doctrine with the Great Church of Christ in Constantinople and with every other Church of Christ of the same doctrine, observing unwaveringly, as they do, the holy apostolic and syn- odal canons and sacred traditions. It is autocephalous and is administered by the Holy Synod of serving Bishops and the Permanent Holy Synod originating thereof and assembled as specified by the Statutory Charter of the Church in compliance with the provisions of the Patriarchal Tome of June 29, 1850, and the Synodal Act of September 4, 1928.

2. The ecclesiastical regime existing in certain districts of the State shall not be deemed contrary to the provisions of the preceding paragraph.

3. The text of the Holy Scripture shall be maintained unaltered. Official translation of the text into any other form of language, without prior sanction by the Autocephalous Church of Greece and the Great Church of Christ in Constantinople, is prohibited.”[16]

It is believed that the role played by Orthodoxy in the Balkans within the framework of the impact of religion in modern democratic government forms should be examined closely in the coming periods. It is possible to say that the European Union is one of the organizations that should ponder the most about this issue.

*Photo: Montenegrin Orthodox Church

[1] Vladimír Baar et al., “Theopolitics of the Orthodox World—Autocephaly of the Orthodox Churches as a Political, Not Theological Problem,” Religions 13, no. 2 (February 2022): 116, https://doi.org/10.3390/rel13020116.

[2] Yoav Schaefer, “Between Political Theology and Theopolitics: Martin Buber’s Kingship of God,” Modern Judaism - A Journal of Jewish Ideas and Experience 37, no. 2 (May 1, 2017): 231–55, https://doi.org/10.1093/mj/kjx023.

[3] Petros Vassiliadis, “Orthodox Christianity,” in God’s Rule: The Politics of World Religions, ed. Jacob Neusner (Georgetown University Press, 2003), 85–105.

[4] Frank Leslie Cross and Elizabeth A. Livingstone, The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church (Oxford University Press, 2005), 1197.

[5] Baar et al., “Theopolitics of the Orthodox World—Autocephaly of the Orthodox Churches as a Political, Not Theological Problem,” 18.

[6] Baar et al., 19.

[7] Paul Werth, “Georgian Autocephaly and the Ethnic Fragmentation of Orthodoxy,” Acta Slavica Iaponica 23 (2006): 27.

[8] Paschalis Kitromilides, Religion and Politics in the Orthodox World: The Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Challenges of Modernity (Routledge, 2018), 35.

[9] Baar et al., “Theopolitics of the Orthodox World—Autocephaly of the Orthodox Churches as a Political, Not Theological Problem,” 2.

[10] Kitromilides, Religion and Politics in the Orthodox World, 36.

[11] Kenneth Morrison, Montenegro: A Modern History (London: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd, 2009), 129.

[12] Morrison, 136.

[13] “Patriarch Bartholomew: We Will Never Give Autocephaly to the ‘Montenegrin Church,’” Orthodox Christianity, December 31, 2019, https://orthochristian.com/126846.html.

[14] Predrag Milic, “Montenegrin Government Falls over Ties with Serbian Church,” Washington Post, August 19, 2022, sec. World, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/montenegrin-government-falls-over-ties-with-serbian-church/2022/08/19/7320e974-2018-11ed-9ce6-68253bd31864_story.html.

[15] Kenneth Morrison, “Church Pact Heralds Fall of Montenegrin Government,” Transitions, August 24, 2022, sec. Politics, http://tol.org/client/article/church-pact-heralds-fall-of-montenegrin-government.html.

[16] Parliament of Greece, “Constitution of Greece,” 1975, art. III, http://www.hri.org/MFA/syntagma/artcl25.html#A3.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

MUNICH SECURITY CONFERENCE 2020 REVEALS THE NECESSITY OF "CONSTRUCTIVE EURASIANISM"

MUNICH SECURITY CONFERENCE 2020 REVEALS THE NECESSITY OF "CONSTRUCTIVE EURASIANISM"

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 21.02.2020 -

IS GREECE A CHINA’S “TROJAN HORSE” OR “DRAGON’S HEAD” IN EUROPE?

IS GREECE A CHINA’S “TROJAN HORSE” OR “DRAGON’S HEAD” IN EUROPE?

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 15.11.2019 -

TURKEY HAS ASSUMED THE CHAIRMANSHIP-IN-OFFICE OF THE SOUTH EAST EUROPE COOPERATION PROCESS (SEECP)

TURKEY HAS ASSUMED THE CHAIRMANSHIP-IN-OFFICE OF THE SOUTH EAST EUROPE COOPERATION PROCESS (SEECP)

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 17.07.2020 -

MESUT ÖZIL’S RESIGNATION STATEMENT UNVEILS THE OPEN SECRET OF LATENT RACISM AND BLATANT DISCRIMINATION IN GERMANY

MESUT ÖZIL’S RESIGNATION STATEMENT UNVEILS THE OPEN SECRET OF LATENT RACISM AND BLATANT DISCRIMINATION IN GERMANY

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 07.08.2018 -

THE EU'S ENLARGEMENT PARADOX: POLITICS OVER PRINCIPLES?

THE EU'S ENLARGEMENT PARADOX: POLITICS OVER PRINCIPLES?

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 25.01.2024

-

TAIWAN’S SOVEREIGNTY AND “ONE CHINA” DILEMMA

TAIWAN’S SOVEREIGNTY AND “ONE CHINA” DILEMMA

Şevval Beste GÖKÇELİK 19.12.2022 -

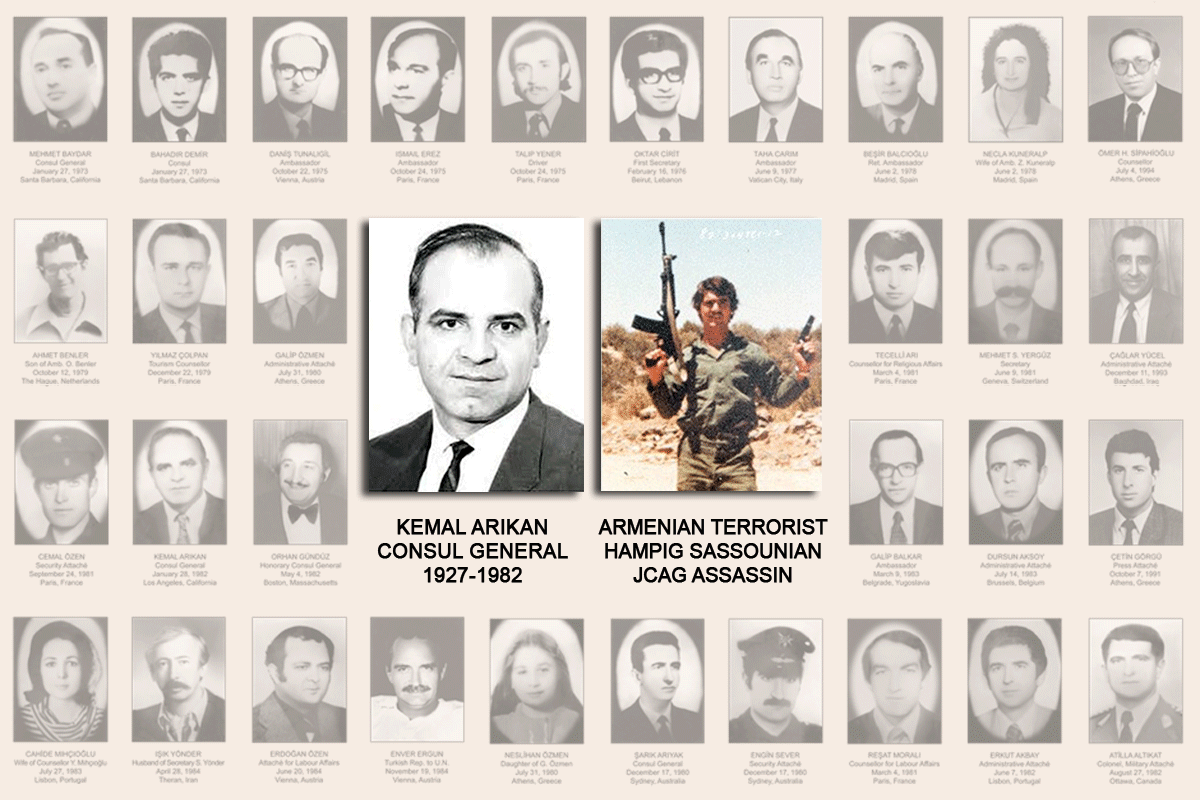

THE DECISION TO RELEASE SASSOUNIAN

THE DECISION TO RELEASE SASSOUNIAN

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 16.03.2021 -

STIMULUS ACTIONS ARE NEEDED FOR NEW ARMS CONTROL AND DISARMAMENT MINDSET IN EURASIA

STIMULUS ACTIONS ARE NEEDED FOR NEW ARMS CONTROL AND DISARMAMENT MINDSET IN EURASIA

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 11.11.2019 -

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA FACES THE EXISTENTIAL THREAT OF SEPARATISM

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA FACES THE EXISTENTIAL THREAT OF SEPARATISM

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 09.11.2021 -

AT THE CROSSROADS: TÜRKİYE AND THE BATTLE FOR BLACK SEA ORDER

AT THE CROSSROADS: TÜRKİYE AND THE BATTLE FOR BLACK SEA ORDER

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 21.10.2025

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"