July 24th is the 93rd anniversary of the Peace Treaty of Lausanne (in this text, the “Lausanne Peace Treaty” will be referred to as the “Lausanne Treaty”). The Lausanne Treaty is an important international contract that was negotiated, signed, and ratified by almost all important participants of the First World War. It is not only a crucial treaty due to the identity of the participating countries, but it is also crucial due to the scope of subject areas it covers. It is a treaty that covers political, military, economic, and humanitarian issues that appertains to the Ottoman Empire and Eastern Front of the First World War.[1] It would not be farfetched to argue that it does not only effect the signatory countries, but has wide ranging ramifications for third countries. Any demands for revision, alteration, or termination of such a treaty must be met with utmost skepticism. This is especially valid for demands that are not based on any principle and rules mentioned in the treaty itself or that are contrary to the general principles of international law. Thus, any subjectively motivated claims regarding this treaty, including those of the Republic of Armenia and the Armenian diaspora rooted in the events of 1915 must be reviewed and evaluated on the basis of the above mentioned context.

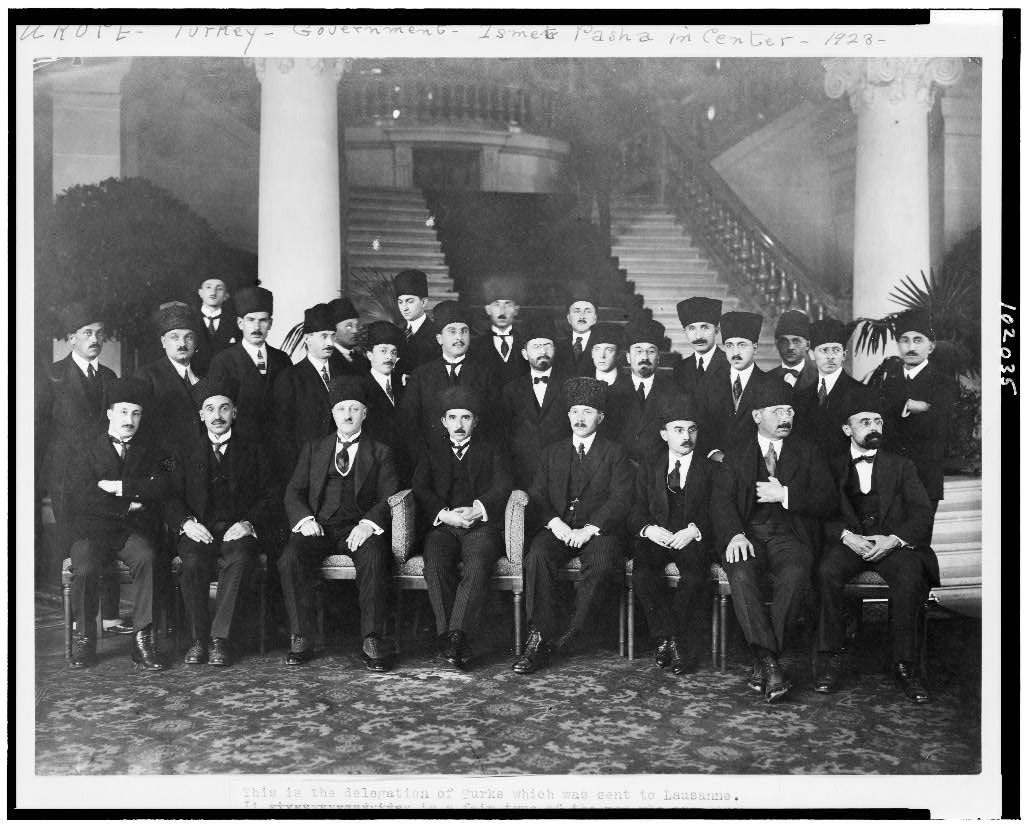

Lausanne Treaty was concluded within the framework of the Lausanne Conference. The three Allied states, Britain, France, and Italy, also acting on behalf of Japan, issued an invitation to Turkey to attend the Lausanne Conference.[2] The conference convened “for the purpose of bringing full peace to the East”.[3]

The Conference was known officially as “The Lausanne Conference on the Questions of the Near East” (from now onwards, “the Lausanne Conference” will be referred as “the Conference”). The Lausanne Treaty was signed after the conclusion of two parts. The first part was held between November 21, 1922 and February 4, 1923. The second part was held between the dates of April 23, 1923 and July 24, 1923.

The participating states to the Conference can be placed in four broad categories. The first category is comprised of the inviting states. Britain, France, Italy and Japan can be placed in this category. The second category is made up of states that have been invited to all the negotiating sessions. Greece, the Serb-Croat-Sloven State, Romania and the United States fall into this category. The third category consists of states which have been invited only to negotiations regarding specific borders. In this category Soviet Russia and Bulgaria were invited to the negotiations regarding the Turkish Straits. In addition to the Turkish Straits negotiations, Bulgaria was also invited to the negotiations regarding the frontier in Thrace. The fourth category consists of states which were invited to dealing with specific topics such as trade and residency. Belgium and Portugal are states that fall into this category. It should be underlined that Turkey was invited to the conference as the main participant state.[4]

It would appropriate to briefly outline the end results of the Conference. This is crucial due to the complex nature of the negotiations. The Conference has produced not one, but 18 related but separate documents (for the purposes of this text, these documents will be referred as “the Documents” with a capital D). The Final Act, which is in fact the 18th Document of the Conference, sheds light on the above mentioned intricate structure and lists the previous 17 Documents which were drawn up in the Conference. These 17 Documents and the Final Act (the 18th Document) together can be considered as a “package of Documents” decided on and signed at the Conference. Among these Documents, the first Document mentioned in the Final Act as “The Treaty of Peace signed on 24 July 1923” can be considered as having particular importance for all the signatories.[5]

It should be noted that, due to the complex nature of the negotiations, the status of the participating states and the number of documents that have been produced at the end of the Conference, the package of Documents is referred to by different names in different publications. “Lausanne Treaty”, “Treaty of Lausanne”, “Lausanne Peace Treaty” are among these terms. This text will use the “Lausanne Treaty” when referring to the package of Documents.

In order to better understand the nature and the content of the Conference, it might be useful briefly to refer to the Final Act since it explains competently the purpose of the conference. In the preamble of the Final Act it is stated that:

The Government of the British Empire, France and Italy, in agreement with the government of Japan, being desirous of finally re-establishing peace in the East, and having invited on the one hand Greece, Romania, the Serb-Croat-Sloven State, and also the United States of America, and on the other hand Turkey, to examine together the arrangements by which a result equally desired by all the nations might be achieved.

The events of 1915 were discussed in this framework. It should be mentioned that in the text of Lausanne Treaty, there are no direct references to Armenians. This is important, since the conflict in which the Armenians took a part in had been a preoccupation of the last period of Ottoman history.[6] Nor can one find a direct reference to Republic of Armenia in the Documents of the Conference. This does not, however, imply that the problems that had arisen after the events of 1915 have not been dealt with in the Conference. In fact, the problems that had arisen from the events of 1915 have actually been thoroughly dealt with both during the negotiation phase and also the text of the Lausanne Treaty.

A differentiating characteristic of the negotiation phase and the texts of Documents concluded in the conference should be noted. During the Conference, the problems that rose from the events of 1915 were dealt with directly. In the Documents, meanwhile, the problems that had arisen from the events of 1915 have been dealt with indirectly.

One issue that had risen from the events of 1915 was regarding territorial demands. This was dealt with directly during the Conference. The representatives of the Allied Powers brought up this topic on several occasions. The Minorities Sub-commission meeting held on December 14 was one such occasion. The representatives of the Allied Powers wanted a detailed discussion on the matter of "A National Homeland for the Armenians" that would start the next day (December 15). The meeting on December 14, however, ended at an impasse.[7]

According to the minutes of the proceedings, the Turkish representative informed the Allied representatives that the Turkish delegation would not allow such a discussion to take place. The Allied representatives, comprising of British, French, and Italian members insisted on the discussions on this matter to go forward. They furthermore demanded that Turkey, instead of refusing to discuss the issue, should present counter arguments to convince the commission. The Turkish representative argued that the issue had been resolved in the prior treaties that were signed between the relevant states. What is referred to here are the following: Treaty of Alexandropol (1920), Treaty of Moscow (1921), and the Treaty of Kars (1921). The initial discussion for "A National Homeland for the Armenians" ended on December 18. In the draft proposal that was accepted as the basis of further negotiations, the question of Armenian homeland was not included.[8]

Despite this agreement, the Allied representatives continued with their efforts in trying to raise the issue for an Armenian homeland. In connection with these efforts, an Armenian delegation was invited to the meeting of the Sub-commission on December 26. Turkish representatives again objected to this invitation on two grounds. First, the representatives argued that the any delegation must be invited to the Sub-commission meetings after a unanimous decision. Second, an Armenian delegation could only be heard if all the minorities residing in Romania, Serbia, and Greece could send a delegation to the Sub-commission meeting. Furthermore, the Turkish representative argued that, in the context put forth by the Allied representatives, the commission also needed to grant a hearing to the delegations of Muslim nations (this was a reference to the Muslim nations living under Allied Powers’ occupation), and an Irish delegation.[9]

Despite these objections of the Turkish representatives, the Allied representatives on the Sub-commission listened to an Armenian delegation on December 26. The Turkish delegation rejected to participate in this meeting. This meeting was not included in the minutes of conference due to the absence of Turkish representatives and the session therefore lacked any official standing. The pressure on the Turkish representatives continued with the declaration made by the American delegation regarding a homeland for the Armenians on December 30. These issues would not be discussed again by the Sub-commission.

These attempts at directly including the Armenian delegation to the Lausanne Conference and issues arising from the events of 1915 yielded no result. By the end of the Conference, not only for Turkey, but also for the Allied Representatives, the subject matter of allocating territory for an Armenian homeland was considered closed.[10]

In the text of the Lausanne Treaty, issues related to the Armenian population have been dealt with indirectly. Despite the indirect manner, the issues pertaining to the Armenian population and problems arising from the relocation and resettlement of Armenians in 1915-16 were actually thoroughly dealt with in text of Lausanne Treaty.

One of the issues that has been dealt with indirectly in the text of the Lausanne Treaty is about the future of displaced individuals as a result of the First World War. The Treaty ensures that no individual who had been displaced was left without a nationality (citizenship). The Treaty does this in two ways. In Article 30 of the Treaty the following is stated:

Turkish subjects habitually resident in territory which in accordance with the provisions of the present Treaty is detached from Turkey will become ipso facto, in the conditions laid down by the local law, nationals of the State to which such territory is transferred.[11]

Article 30 ensures that any individual who was left outside the acknowledged borders of the Lausanne Treaty would automatically gain the nationality of the country in which they were residing at the signing of the Lausanne Treaty.

It is further added in Article 31:

Persons over eighteen years of age, losing their Turkish nationality and obtaining ipso facto a new nationality under Article 30, shall be entitled within a period of two years from the coming into force of the present Treaty to opt for Turkish nationality.[12]

Article 31 states unequivocally that any individual who had acquired a new nationality at the signing of the Treaty would have the right to regain Turkish nationality.

A second issue that has been dealt with indirectly in the text of the Lausanne Treaty is about the immovable property of the displaced individuals. It is stated in Article 33:

Persons who have exercised the right to opt in accordance with the provisions of Article 31 and 32 must, within the succeeding twelve months, transfer their place of residence to the State for which they have opted. They will be entitled to retain their immovable property in the territory of the other State where they had their place of residence before exercising their right to opt…[13]

The issue of immovable property of the displaced individuals has been dealt with in the Amnesty Declaration (the 8th Document). In Article 6, it is stated that:

The Turkish Government which shares the desire for general peace with all the Powers, announces that it will not object to the measures implemented between 20 October 1918 and 20 November 1922, under the protection of the Allies, with the intention of bringing together again the families which were separated because of the war, and of returning possessions to their rightful owners.[14]

This article further states that these efforts by the Allied forces could hinder any individual from reapplying to the proper authorities regarding their ownership rights of their properties. According to the documents from the Archives of the USA, 644,900 Armenians had returned to the land that is now referred to as Turkey before the signing of the Lausanne Treaty. The number of properties returned to their owners had already reached 241,000 by 1919. This number correspondence to almost 98 per cent of the immovable properties.[15]

A third issue that has been again dealt with indirectly is about the political and military actions that were taken and commissioned between the dates of August 1, 1914 and November 20, 1922. The first five articles of the Amnesty Declaration deals with these issues. In Article I and Article III, it is stated that nationals (citizens) or individuals residing in Turkey and Greece could not be held accountable for or be prosecuted for their political and military actions (including aiding and abetting foreign powers) between the above mentioned dates. In Article II, it is stated that individuals residing in countries which were separated from Turkey also could not be prosecuted for their actions between the above mentioned dates. Just like in Article I and III, these individuals were given amnesty for both political and military actions. Article IV provides protection from prosecution to the nationals of all signatories of Lausanne Treaty for their political and military actions commissioned between the aforementioned dates.[16]

As it was stated previously, Lausanne Conference Documents in nowhere contain any provisions concerning the problems that have arisen due to the events of 1915. Nevertheless, the issue was thoroughly dealt with during the Conference. In the text of the Documents, problems that had arisen due to the events of 1915 have been dealt without making any specific reference to a particular ethnic or national group. This is important, since it does not place any particular group’s suffering above another group’s suffering. The problems that had arisen due to the events of 1915 had devastating effects on all the peoples of the region. This is a fact whether one belongs to the Muslim or Christian faith, or whether one was a Turk or Armenian. This is why the Conference and the Documents produced at the end of the Conference have such a crucial importance.

It should be underlined that the comprehensive system created by this Conference and the Documents closed all “the Questions of the Near East” that had stemmed from the First World War.

Bibliography

Aktan, G. “The Lausanne Peace Treaty and the Armenian Question”. Retrieved from Center For Euroasian Strategic Studies. The Armenian Question: Basic Knowledge and Documentation. Retrieved on 09 July 2016, http://www.eraren.org/bilgibankasi/en/index1_1_2.htm

Lozan Barış Andlaşması: Lozan'da İmzalanan Sözleşmeler, Senetler, Barış Andlaşması Ekli Mektuplar ve Montrö Boğazlar Sözleşmesi. İcra Sekreterliği ed., Republic of Turkey, Ministry of Foreign Affairs 1984.

Lozan Barış Konferansı: Tutanaklar ve Belgeler. (1970). Vol. 1. Ankara: Ankara Üniversitesi Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi Yayınları.

Oran, B. (2010). “1919-1923: The Time of Liberation” (M. Akşin, Trans.). In B. Oran (Ed.), Facts and Analysis with Documents (pp. 53-142). Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press.

Pazarcı, H. (2015). Türk Dış Politikasının Başlıca Sorunları (1st edition). Ankara: Turhan Kitabevi Yayınları.

Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2011). Lausanne Peace Treaty. Retrieved from http://www.mfa.gov.tr/lausanne-peace-treaty-part-i_-political-clauses.en.mfa

Tacar, P., & Gauin, M. (2012). “State Identity, Continuity, and Responsibility: The Ottoman Empire, the Republic of Turkey and the Armenian Genocide: A Reply to Vahagn Avedian”. The European Journal of International, 23(3), p. 821-835. doi:10.1093/ejil/chs047

Turan, Ö. (2001). “The Armenian Question at the Lausanne Peace Talks”. In T. Ataöv (Ed.), The Armenians in the Late Ottoman Period (2 ed., pp. 207-239). Ankara: The Turkish Historical Society for The Council of Culture, Arts and Publications of the Grand National Assembly of Turkey.

*Photo: https://loc.gov/

[1] Aktan, The Lausanne Peace Treaty and the Armenian Question

[2] Lausanne Treaty was concluded within the framework of the Lausanne Conference.

[3] Oran, “1919-1923: The Time of Liberation”, p. 126.

[4] Oran, “1919-1923: The Time of Liberation”, p. 129; Gönlübol, p. 51.

[5] Oran, “1919-1923: The Time of Liberation”, p. 129.

[6] Turan, “The Armenian Question at the Lausanne Peace Talks”, p. 238.

[7] Turan, “The Armenian Question at the Lausanne Peace Talks”, p. 220.

[8] Turan, “The Armenian Question at the Lausanne Peace Talks”, p. 219-222

[9] Turan, “The Armenian Question at the Lausanne Peace Talks”, p. 221-222

[10] Lausanne Peace Conference Proceedings, p. 151-292.

[11] Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Lausanne Peace Treaty.

[12] Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Lausanne Peace Treaty.

[13] Republic of Turkey Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Lausanne Peace Treaty.

[14] Tacar and Gauin, “State Identity, Continuity, and Responsibility…”, p. 832.

[15] Tacar and Gauin, “State Identity, Continuity, and Responsibility…”, p. 832.

[16] Pazarcı: Türk Dış Politikasının Başlıca Sorunları, p. 43; Tacar and Gauin, “State Identity, Continuity, and Responsibility…”, p. 832-833; Lozan Barış Andlaşması (1984).

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

EP TURKEY RAPPORTEUR PIRI CONFIRMS WHAT HAD ALWAYS BEEN SUSPECTED: “EVEN IF TURKEY WERE A PERFECT DEMOCRACY, MERKEL AND […] SARKOZY WOULD NOT WANT TURKEY IN THE EU”

EP TURKEY RAPPORTEUR PIRI CONFIRMS WHAT HAD ALWAYS BEEN SUSPECTED: “EVEN IF TURKEY WERE A PERFECT DEMOCRACY, MERKEL AND […] SARKOZY WOULD NOT WANT TURKEY IN THE EU”

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 04.04.2019 -

CONCERTED EFFORTS TO DOWNPLAY THE MILESTONES OF THE REPUBLIC OF TÜRKİYE AND TURKISH HISTORY

CONCERTED EFFORTS TO DOWNPLAY THE MILESTONES OF THE REPUBLIC OF TÜRKİYE AND TURKISH HISTORY

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 14.06.2023 -

GREEK POLICIES TOWARDS TURKISH MINORITY SCHOOLS RISK REPEATING HISTORY

GREEK POLICIES TOWARDS TURKISH MINORITY SCHOOLS RISK REPEATING HISTORY

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 19.08.2025 -

FRANCE WITH MACRON: THE DESTABILIZING FACTOR IN THE BALKANS

FRANCE WITH MACRON: THE DESTABILIZING FACTOR IN THE BALKANS

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 01.11.2019 -

BALKANS 2016: INTEGRATION EFFORTS IN A TIME OF UNCERTAINITY

BALKANS 2016: INTEGRATION EFFORTS IN A TIME OF UNCERTAINITY

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 09.01.2017

-

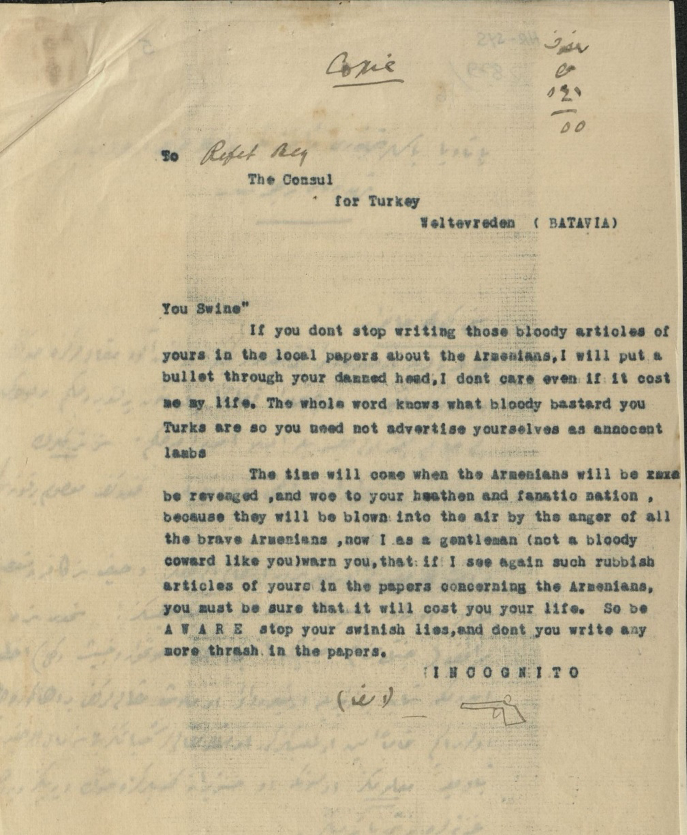

FROM DISTANT FRONTIERS TO A LONG CHAIN OF EXTREMISM: MEHMET REFET BEY AND EARLY ARMENIAN TERRORISM (1916)

FROM DISTANT FRONTIERS TO A LONG CHAIN OF EXTREMISM: MEHMET REFET BEY AND EARLY ARMENIAN TERRORISM (1916)

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 11.02.2026 -

NEW LEADERS FOR THE EUROPEAN UNION HAVE BEEN APPOINTED

NEW LEADERS FOR THE EUROPEAN UNION HAVE BEEN APPOINTED

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 06.08.2019 -

THE 16TH BRICS SUMMIT REGARDING CHINA AND THE GLOBAL SOUTH

THE 16TH BRICS SUMMIT REGARDING CHINA AND THE GLOBAL SOUTH

Seyda Nur OSMANLI 26.12.2024 -

BREXIT: NEW PARADIGM SHIFT FOR GLOBALIZATION AND SIGNAL FOR NEW WORLD ORDER

BREXIT: NEW PARADIGM SHIFT FOR GLOBALIZATION AND SIGNAL FOR NEW WORLD ORDER

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 27.01.2017 -

BECOMING THE PART OF THE PROBLEM: THE FAULTY POLICIES OF THE WEST IN EURASIA AND THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

BECOMING THE PART OF THE PROBLEM: THE FAULTY POLICIES OF THE WEST IN EURASIA AND THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 11.08.2015

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"