Uluslararası Suçlar ve Tarih / International Crimes and History

| Number | : | 16 |

|---|---|---|

| Year | : | 2015 |

| Price | : | 17.00 TL |

Download PDF

One of the most determined and loudest-voiced opposition to the Russian annexation of Crimea in March 2014 came from the Crimean Tatars, a Turkic people indigenous to Crimean peninsula. At the same time, the Russian authorities took rigorous measures to crack down the Crimean Tatar opposition and its leadership. What is the reason of the resistance of the Crimean Tatars not only in Crimea but around the world to the annexation of Crimea by the mighty Russia? After all, in Ukraine, before the annexation, Crimean Tatars were an underprivileged group and the target of prejudices in the societal domain. Although Ukrainian governments took some steps for the recognition of the Crimean Tatars and their rehabilitation, these were attempts far from being satisfactory. Likewise, one may ask what rationale Russia follows in its punitive oppression of the Crimean Tatars. The answers should be found in geopolitics and history.

For the powers that seek to establish their hegemony on what is today referred to as the Wider Black Sea Region, Crimea is a strategically important spot in the north of the Black Sea. For this reason, since the eighteenth century, Russia has sought to take hold of the Crimean peninsula to establish a base to open up to warm waters of the south. Yet, the mere control the Crimean peninsula was never seen sufficient. What Russia sought in Crimea has been the Russification of the peninsula, which, at the same time, meant its de-Tatarization. In fact, the recent oppression of the Crimean Tatars should be viewed as a continuation of this centuries-long policy.

With the detachment of Crimea from the Ottoman Empire by the Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca in 1774 and the following annexation of Crimea in 1783 by the Russian Empire, a state-led colonization of the Crimean Peninsula by the Slavs, and other troubles such as gradual exclusion from the urban life, loss of control over the land, denial of the opportunity to be represented in governmental offices, and the continual exodus from the Crimean Peninsula had been the burdensome circumstances that the Crimean Tatars found themselves trapped in. The experiences of the Crimean Tatars under Soviet rule were no less difficult. Initially, the Soviets gave assurances for national self-determination and protection of Muslim religious rights to gain support of the masses. However, before long, protection of national and religious life and the principle of self-determination were exchanged with the primacy of the establishment of the ‘Proletariat Dictatorship’. Accordingly, Soviet-style ‘Tatarization’ policies were renounced that was followed by the purges. In 1944, Crimean Tatars were deported en masse to Central Asia. This deportation (Sürgün [exile], in the Crimean Tatar lexicon) destroyed the Crimean Tatar life in the Crimean Peninsula, while leaving thousands perished on the way and after arrival to locations of exile. The devastation was so enormous that some Crimean Tatar activists, as well as some scholars, interpret the Sürgün as a genocide. On the whole, for the Crimean Tatars the last two-centuries meant a long period of exclusion, discrimination, marginalization, and exile. The almost 200-year long ethnodemographic engineering in the Crimean peninsula left deep wounds both in the body and the memory of the Crimean Tatars. The recent annexation, besides the very real human rights violations, has made the wounds in the memory of the Crimean Tatars bleed again. In order to gain a better grasp of the fears and the reactions of the Crimean Tatars in Crimea, other parts of Ukraine, and diaspora to the Russian annexation of Crimea in March 2014, these fears and reactions should be contextualized within this history.

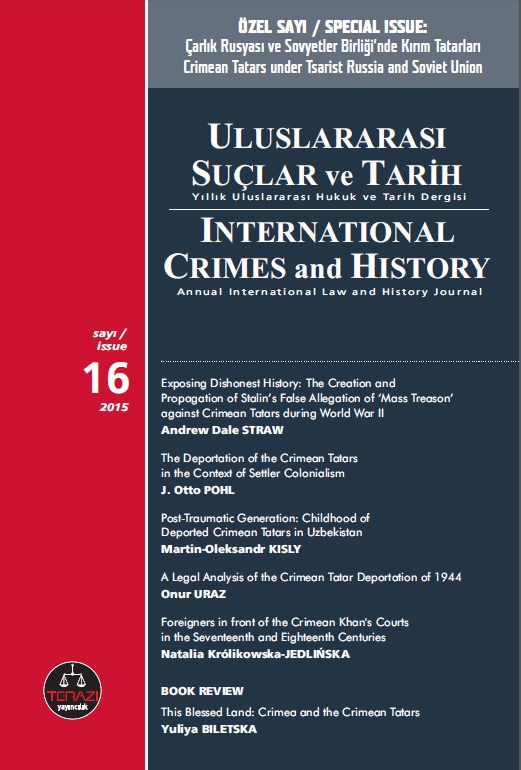

Upon this background, the present issue of International Crimes and History is mainly dedicated to studies that examine various aspects of the Sürgün of the Crimean Tatars in 1944. As is well-known, the pretext of the Sürgün was the alleged mass collaboration of the Crimean Tatars with the Nazi invaders. This allegation was propagated by the Soviet propaganda machine in such an effective way that even today the myth of the mass Crimean Tatar treason is widespread among the post-Soviet nations. Andrew Dale Straw, in his article titled Exposing Dishonest History: The Creation and Propagation of Stalin’s False Allegation of ‘Mass Treason’ against Crimean Tatars during World War II examines the formation and propagation of this allegation and presents a counter-narrative.

There have been numerous cases of forced deportations as a collective punishment of the unwanted racial, ethnic, national or religious groups throughout the history. In fact, there is a huge literature on this kind of tragedies that were affected by the colonial powers in the Americas, Africa, Australia and the Middle East. However, the 1944 Crimean Tatar Deportation has not yet become a part of this literature, which could have provided the research community with better conceptual tools and a comparative perspective. J. Otto Pohl in his article titled The Deportation of the Crimean Tatars in the Context of Settler

Colonialism analyzes the Crimean Tatar case in reference to “settler colonialism” in different parts of the world with this perspective.

Until now, the 1944 Crimean Tatar Deportation has been the subject of a number of studies. Many of these studies provided ‘macro-histories’ of the Sürgün. Although the importance of these studies cannot be overlooked and similar studies shall continue, the micro-history of the Sürgün also awaits to be written. Particularly, studies employing new historiographical approaches would contribute to a deeper understanding of the experience of the Sürgün. Moreover, given that the social memory of the Sürgün is one of the building blocks of the contemporary Crimean Tatar identity, studies on the formation of the social memory of the Sürgün through the stories told in public and private spaces, as well as the subjective experiences of the Crimean Tatars as they went through the deportation and life in exile would open new ways for a deeper understanding of not only the Sürgün, but also its effect on the formation of the Crimean Tatar identity. Martin-Oleksandr Kisly in his article titled Post-Trumatic Generation: Chilhood of Deported Crimean Tatars in Uzbekistan, which aims to

comprehend some aspects of the experiences of the Crimean Tatars who lived their childhood in exile through the testimonies he collected is an important step in this direction.

As stated above, the devastation of the Sürgün was so big that today some Crimean Tatars and scholars regard it as a genocide and some Crimean Tatar activists seek the recognition of the Sürgün as such by the global public. As regards to that, on November 12th, 2015, the Ukrainian parliament recognized the devastation of the Crimean Tatars by the 1944 Sürgün as genocide. Onur Uraz’s article titled A Legal Analysis of the Crimean Tatar Deportation of 1944 provides a detailed legal analysis of the Sürgün that seeks to answer whether 1944 Crimean Tatar Deportation could legally be characterized as genocide or crime against humanity.

Again, as stated above, since the last two centuries or so, Russian authorities have been trying to erase the traces of the Crimean Tatar heritage in Crimea. One of the ways that both the Tsarist Russia and the Soviet Union employed to achieve this goal had been to present the Crimean Tatars as ‘uncivilized barbarians’ who needed to be civilized by the ‘enlightened Russians’. However, this representation is at odds with historical realities. The Crimean Khanate that lasted from 1449 to 1779 was based on an established and complicated polity and social system. Moreover, after its annexation by the Tsarist Russian in 1983, Crimea continued to be a cultural and intellectual center and produced a number of intelligentsia, who transmitted modern Western ideas and ideals to the Ottoman Empire and the Islamic world. Natalia Krolikowska-Jedlinska in her article titled Foreigners in front of the Crimean Khan’s Courts in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries examines three cases in which foreigners appeared in the Crimean Khanate courts, which reveals that, in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, there was an established and functioning legal system in the Crimean Khanate in the standards of those times.

Finally, Yuliya Biletska provides an instructive review of the latest book of Prof. Paul Robert Magocsi, a renowned specialist in the history of Ukraine, titled This Blessed Land: Crimea and the Crimean Tatars published in 2014 by the University of Toronto Press. One last thing to mention in this editorial note is that International Crimes and History is a bilingual journal that publishes articles and book reviews in English and Turkish. However, most of the manuscripts that were submitted for this issue on Crimea and Crimean Tatars under Imperial Russian and Soviet rules came from non-Turkish scholars from different countries. This is most probably a reflection of the increasing interest in the Crimean Tatars both in the social and academic spheres due the recent events taking place in Ukraine and Crimea. This is a promising development that may result in an increase in academic interest on one of the understudied ethno-national groups in the Eurasian region. We hope for a similar increase of interest in other understudied ethnic, national and religious groups in Eurasia. International Crimes and History will be happy to serve as a scholarly platform for such studies.

“Künye/Copyright Page”. Uluslararası Suçlar ve Tarih Dergisi / International Crimes and History Journal 16 (2015): 2.

“İçindekiler/Contents”. Uluslararası Suçlar ve Tarih Dergisi / International Crimes and History Journal 16 (2015): 4.

ARAŞTIRMA MAKALELERİ/RESEARCH ARTICLES

Pohl, J. Otto. “The Deportation of the Crimean Tatars in the Context of Settler Colonialism / Yerleşimci Sömürgeciliği Bağlamında Kırım Tatar Sürgünü”. Uluslararası Suçlar ve Tarih Dergisi / International Crimes and History Journal 16 (2015): 45-70.

Kisly, Martin-Oleksandr. “Post-Traumatic Generation: Childhood of Deported Crimean Tatars in Uzbekistan / Posttravmatik Kuşak: Sürgün Edilen Kırım Tatarlarının Özbekistan’daki Çocuklukları”. Uluslararası Suçlar ve Tarih Dergisi / International Crimes and History Journal 16 (2015): 71-94.

Uraz, Onur. “A Legal Analysis of the Crimean Tatar Deportation of 1944 / 1944 Kırım Tatar Sürgünü’nün Hukuki Değerlendirilmesi”. Uluslararası Suçlar ve Tarih Dergisi / International Crimes and History Journal 16 (2015): 95-138.

Jedlinska, Natalia Królikowska. “Foreigners in Front of the Crimean Khan’s Courts in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries / Onyedinci ve Onsekizinci Yüzyıllarda Kırım Hanlarının Mahkemelerinde Yabancılar”. Uluslararası Suçlar ve Tarih Dergisi / International Crimes and History Journal 16 (2015): 139-54.

KİTAP İNCELEMESİ / BOOK REVIEW

Andrew Straw is an ABD PhD Student in History (European) at the University of Texas, Austin. For the last year and a half, he has been conducting research in Russia for his dissertation on Crimean Tatars titled Resisting Ethnic Cleansing: Crimean Tatars, Crimean and the Soviet Union, 1944-1991. In 2010, he completed a M.A. in Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies at Stanford University. He received his B.A. in 2006, majoring in History and Russian, East European and Eurasian at the University of Texas, Austin. Straw’s research interests include Soviet Union, World War II, Soviet nationalities policies, Islam in the Soviet Union, migration, and Soviet Tourism.

Contact: astraw@utexas.edu

J. Otto Pohl is a Lecturer in the Department of History at the University of Ghana, where he teaches Modern European and World Histories. From 2007 to 2010, Dr. Pohl served as an Associate Professor of International and Comparative Politics at American University of Central Asia in Bishkek. He earned a B.A. (1992) in History from Grinnell College and an M.A. (2002) and Ph.D. (2004) in History from the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. He is the author of two books; The Stalinist Penal System and Ethnic Cleansing in the USSR, 1937–1949. He has also written a number of shorter pieces on the subject of national deportations in the USSR.

Contact: j.ottopohl@gmail.com

Martin-Oleksandr Kisly graduated from the Department of History at the University of Kyiv in 2012. He earned his Master’s Degree in 2014 from the Department of History at Kyiv-Mohyla Academy with his thesis entitled Childhood of Crimean Tatars in Exile. Kisly is currently a Ph.D Candidate at the same department. In his doctoral research, he focuses on the Crimean Tatar identity in exile. Kisly’s research interests include memory studies, oral history, imagology and identity studies.

Contact: martin.oleksandr@gmail.com

Onur Uraz is a PhD fellow in Public International Law at the University of Southampton. His current research focuses on interpretation and application of the genocide law. Uraz gained his LL.B. Degree from Gazi University in 2011, and completed his LL.M. Degree in 2014 at the University of Glasgow. Uraz was qualified as an attorney at the Ankara Bar Association in 2012. He is a member of the Centre for Law, Ethics and Globalisation (LEAG) at the University of Southampton. His research interests are international criminal law, international and European human rights law, international adjudication and Turkish criminal law.

Contact: onururaz215@yahoo.com.tr

Natalia Królikowska-Jedlińska (PhD in History at the University of Warsaw, 2010) is an Assistant Professor in the Institute of History of the University of Warsaw. Królikowska-Jedlińska’s publications include Crimean Crime Stories: Cases of Homicide and Bodily Harm during the Reign of Murad Giray (1678-1683) (in The Crimean Khanate between East and West (15th-18th Centuries), ed. Denise Klein, Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 2012, pp. 109– 124) and The Law Factor in Ottoman-Crimean Tatar Relations in Early Modern Period (in Law and Empire: Ideas, Practices, Actors, ed. Jeroen Duindam, et al., Brill, Leiden-Boston 2013, pp.177–195). Her research focuses on Crimean, Ottoman and Caucasian histories in the Early Modern Period.

Contact: nkrolikowska@uw.edu.pl

Yuliya Biletska is an Assistant Professor in International Relations Department at Karabuk University, where she teaches undergraduate and graduate courses on collective memory, nationalism and political and economic transitions in Post-Soviet counties. She completed her MA in Eurasian Studies at Middle East Technical University and Ph.D. studies in Political Science (Ethnopolicy and Ethnic Studies) at Taurida National

V.I. Vernadsky University. During her doctoral studies, she had been a research fellow at Middle East Technical University, where she studied the impact of Turkey on the ethnic identification of the Crimean Tatars in Crimea. Her research interests include ethnic identities, minority rights, nationalism, migration, collective memory, and multiculturalism.

Contact: yuliyabiletska@karabuk.edu.tr