DrPatWalsh.com (29 July 2018)

Dr. Pat WALSH

On 19 June 1919 T.P. O’Connor, MP, spoke at a meeting held in Central Hall, Westminster, in support of the Armenian cause. O’Connor appeared on the platform with Lord James Bryce, Lord Gladstone (son of William), G.P. Gooch (famous historian) and the Armenian General Andranik. A record of the proceedings was published in a pamphlet, Armenia and the Settlement, by the Armenian Bureau in London.

O’Connor was one of the last remaining Redmondite MPs left in the British House of Commons, after Sinn Fein had destroyed the Irish Parliamentary party in the 1918 election. The Irish had rejected O’Connor’s party after it had gone over to Imperialism and recruited Irishmen in their hundreds of thousands to die and kill in Britain’s Great War on Germany and Ottoman Turkey.O’Connor had supported the war because England had promised Irish Home Rule in return for war-recruiting by his party. But five years later there was no sign of Home Rule, Britain had rejected the vote by the Irish democracy for an independent Republic and it was governing Ireland through military repression.

T.P. O’Connor had been a long-standing supporter of the Armenians, and an anti-Turk in the Gladstonian “bag and baggage” tradition. He supported Russian “liberation” of the Armenians in the 1877/8 war. He was not only an M.P. for Liverpool in England but had a successful journalistic career in English Liberal circles.

O’Connor is also noteworthy as the inspirer of Wellington House, the secret British Department of State, set up under Charles Masterman, to conduct a massive propaganda campaign against the Germans and Turks through distinguished historians and literary figures (This information about O’Connor’s role in the foundation of Wellington House is contained in Lucy Masterman’s biography of her husband, p.272). It was Wellington House that published Arnold Toynbee’s ‘Armenian Atrocities, The Murder of a Nation’, which formed the basis of Lord Bryce’s Blue Book, the British Government record of the massacres, produced in 1916.

At the meeting Lord Bryce said that “we should have in Armenia a homogeneous Armenian population including all these territories”. But he didn’t say how. Given that the Armenians constituted a minority in “all these territories” claimed—illustrated in a map of Magna Armenia contained in the pamphlet —one presumes the author of the Blue Book was in favour of extensive ethnic cleansing or worse, to create this “homogeneous Armenia”.

T.P. O’Connor revealed in his speech that he had been fighting for the Armenians for 45 years with Gladstone, the Chairman’s father, and he was angered by newspaper reports of the terms to be given to the Turks (in what became the Treaty of Sèvres):

“Why is it that the terms of the Armistice in the demands on the Turks contrast so favourably with the terms we imposed on the Austrians and Germans?.. when I … read in an English paper of the ‘gentlemanly Turk,’ well Ladies and Gentlemen, I see red. What is the meaning of it all? Is it money? Is it international finance? Whatever the secret is, from this platform, we declare here to-night that we go back to the old policy of our Chairman’s father: ‘Out with them, Bag and Baggage!’ (Applause) I agree with all that Lord Bryce… as to what the future Armenia should be. It ought to be a big Armenia, not a small one.”

Immediately after O’Connor’s speech a resolution was read out pledging those present to supporting “The Future Government of Armenia and the Boundaries of the New State” as claimed by the Armenian delegations at Paris. The claim for the 7 Ottoman vilayets plus Cilicia and Russian Armenia was then read out. A map appears in the pamphlet showing what Magna Armenia represented. It took in about half of Turkey, from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean, most of Georgia and Azerbaijan, and parts of Iran as well as Erivan.

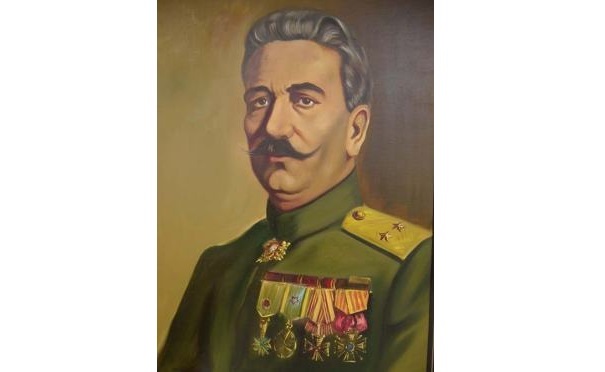

When I originally wrote about this meeting in the book The Armenian Insurrection and the Great War a thought occurred to me: What was the most effective Armenian General, Andranik, doing away from the battlefield at this time?

The war, of course, was far from over. A few months earlier Andranik had, himself, been waging it in a very thorough manner, carving out Greater Armenia through massacre and ethnic cleansing of Moslems in the Caucasus, after he had been driven out of eastern Anatolia by the Turks.

Andranik had a fearsome reputation as an irregular fighter (fedayi). The Armenian publication Andranik – Armenian Hero (Patriot Publishing) details his exploits. He became active against the Ottoman Government and the Kurdish population in the late 1880s in the Hunchak party. He then joined the Dashnaktustyun, participating in the assassination of Constantinople’s chief of police, in 1892. He took part in the Sasun Rising in 1894, which was portrayed as an Ottoman massacre of Armenians but which was actually an inter-ethnic battle between Armenians and Kurds which the Ottoman Army put an end to. It was an event manufactured by the Armenian insurrectionists to provoke foreign intervention on the model of the ‘Bulgarian Horrors’ that had enthralled the Gladstonian Liberals a couple of decades before.

In 1901 Andranik took part in the Battle of Holy Apostles monastery, another attempt to encourage Great Power intervention in the Ottoman state on the Armenian side. This exploit greatly impressed Trotsky at the time. He then took command of another attempted insurrection in Sasun in 1904 which led to the deaths of thousands of Armenians and Kurds before Andranik was forced to flee into Persia by Ottoman forces.

After these failures the ARF/Dashnaks changed tack and went into politics. When the Dashnaks decided to go into the Ottoman parliament and worked with the Young Turks Andranik dissented and went to fight in Bulgaria against the Ottomans, pursuing the “bag and baggage’ policy of driving the Moslem population out of the Balkans.

When the Great War began Andranik commanded the first Armenian volunteer battalion attached to the Tsarist invasion force. He took part in the capture of Van and the massacre of the Moslem population there, as well as the taking of Mush in February 1916.

Annoyed by the Russian decision to demobilise the Armenian battalions after their freelance ethnic cleansing operations and the successful capture of most of eastern Anatolia Andranik resigned and left the front in July 1916.

Things, however, all changed in late 1917 because of events in Russia. Andranik returned and participated in the Armenian administration of occupied eastern Anatolia, authorised by the Provisional Government in Russia. Much killing and ethnic cleansing took place with Russian authority weakened and the Dashnaks in key positions.

Andranik was appointed Major General within the new Armenian Army Corp and he led the unsuccessful defence of Erzurum in early 1918 after the Russian lines dissolved, with the Bolshevik takeover. When the Armenian National Council signed the peace Treaty of Batum with the Ottomans, giving up their demand for Western Armenia and settling for the Erivan Republic in the Caucasus, Andranik took a die-hard position, refused to recognise the Armenian State and set out with his forces to realise the original demand for Magna Armenia.

Andranik took his Special Striking Division of Dashnaks to Nakhchivan, Zangezur and then Karabakh in the Caucasus to extend the territories of the Armenian state he would not recognise. He cosied up to the Bolsheviks after accusing the Armenian Republic of betrayal and declared Nakhchivan part of Soviet Russia. With the arrival of Turkish forces he moved his forces into Zangezor in order to put an Armenian territorial barrier between Turkey and Azerbaijan.

Andranik – Armenian Hero is quite frank about the ethnic cleansing this involved:

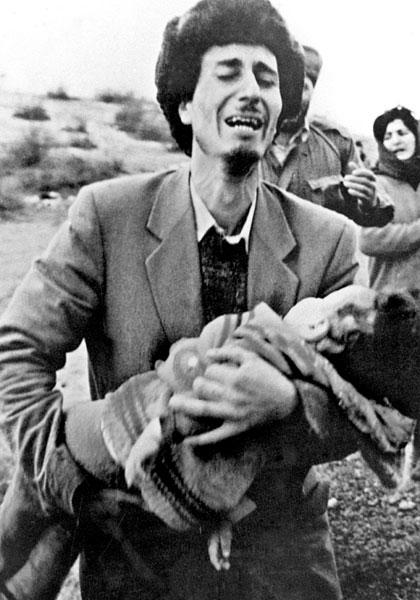

"Andranik’s irregulars remained in Zangezur surrounded by Muslim villages that controlled the key routes connecting the different parts of Zangezur. According to David Bloxham, Andranik initiated the change of Zangezur into a solidly Armenian land by destroying Muslim villages and trying to homogenize key areas areas of the Armenian state. In late 1918 Azerbaijan accused Andranik of killing innocent Azerbaijani peasants in Zangezur and demanded that he withdraw Armenian units from the area. Antranig Chalabian wrote that, “without the presence of General Andranik and his Special Striking Division, what is now the Zangezur district of Armenia would be part of Azerbaijan today…” Andranik’s activities in Zangezur were protested by Ottoman General Halil Pasha, who threatened the Dashnak government with retaliation for Andranik’s actions. Armenia’s Prime Minister Hovhannes said he had no control over Andranik and his forces.”

Despite the Mudros Armistice at the end of October ending the war with the Ottomans Andranik decided to fight on to extend Armenian territory into Azerbaijan. He took his Special Striking Division north-east toward Karabakh and its main town, Shusha. Local Armenians, fearing the worst, attempted to stop Andranik through negotiations with their Moslem neighbours. However, after overcoming Kurdish resistance on the road to Shusha, Andranik was only stopped by British General Thomson in Baku, who informed him that a dim view would be taken of any further activities at the Peace Conference in Paris.

The British warning forced Andranik back to Zangezur. After staying the winter there with his force he was persuaded to surrender his weapons to the Armenian Catholicos in Etchmidzin and go to Europe by the British, to get him out of the way.

When the Armenian (Erivan) Republic was established on May 28, 1918 under “Turkish Protection” and a series of Peace and Amity Treaties were signed between the Ottomans and Armenians on June 4, 1918, revolutionary leaders such as Andranik, Drastamat Kanajan, and Hanazsap refused to abide by the treaties signed by Khatachaznouni. They continued their cleansing operations in Armenia, Azerbaijan and the Caucasus with their own forces. A month after the Mudros Treaty of October 1918 Armenia abolished all treaties they had previously signed with the Ottomans on June 4, 1918 and entered Kars and Ardahan with the permission of the British army in Persia.

However, geopolitical considerations determined that the British curb Antranik’s ethnic cleansing activities in Azerbaijan, where a buffer state was needed against the Bolsheviks.

We have an interesting reaction to all of this from Near East Relief, one of the main U.S. Protestant missionary organisations which promoted Armenian/Christian interests in America against the Ottomans during the period. They were one of the suppliers of anti-Moslem propaganda to the West that fuelled atrocity stories and formed the basis of War Propaganda against the Ottomans in Britain and America.

E.A. Yarrow, Assistant to the Chief of Staff, Near East Relief, in Tiflis wrote an article called The British Withdrawal and Present Conditions in early 1920. He was “bewildered” with the British evacuation from the Caucasus, which had been completed in September 1919. The British had occupied the region for a mere 7 months. Yarrow contended that Britain overall had “did badly” in their occupation in the Caucasus, although, at the same time, he gave them the credit for bringing peace, order and stability to the general area:

“They defined the territories of the different republics, put these territories under the control of constitutional authorities, and adopted the policy of maintaining the status quo.”

What seems to have annoyed Yarrow was the surprisingly impartial attitude of the British military authorities in the Caucasus. They did not favour their former allies, the Armenians, as Yarrow thought they should have. Instead, the Georgians, who had been sympathetic to the German enemy, and the Azerbaijanis, who had sided with the Turks, were given every respect, even at expense of the “Christian nation”.

Yarrow noted, the complaints of his Armenian contacts about the British:

“In the Shusha and Karabagh districts, a detachment of the Armenian army under the leadership of General Andranig was making a successful advance on the Tartars, but were stopped by the British, and Andranig was ‘persuaded’ to take a journey to Paris to take part in the peace negotiations! Nothing has been heard of his actions there.” (The Journal of International Relations Vol.10, No.3, January 1920, pp.251-55)

Yarrow complained that Karabakh had been placed under British authority and was given an Azerbaijani Governor. The Armenians had been disarmed and ammunition taken away from them. Finally Nakhchivan, like Karabakh, was not given to the Armenians, but retained as part of Azerbaijan.

Yarrow believed that the British were intending to off-load the mandate for Armenia to the United States whilst retaining influence over the Baku to Batum Railway, through Azerbaijan and Georgia. He thought such an arrangement "would be deadly” for the mandated Power over Armenia.

Of one thing Yarrow was correct, but not in the way he intended. He forecast that there would be trouble when the British left. The Armenians, supported by the government in Erivan, began an offensive against the Azerbaijani populations of Zangezur, Nakhjivan and Karabakh. It was reported that the Azerbaijani police force in Karabakh had been slaughtered by their Armenian colleagues. This aggression, which necessitated the diversion of the Azerbaijani army to these areas, left the northern border open to the Red Army in April 1920. Not only Azerbaijan but Armenia and Georgia, fell to the Bolsheviks as a result. Lloyd George, stumbling from one crisis to another in the expanded British Empire that had been won through the Great War, did nothing to defend the Caucasian states he had helped create and guaranteed the existence of.

It must be said that in the year following the Mudros Armistice, during 1919, Britain did some good in the Caucasus, stabilising things and bringing about orderly state formation in Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia. Democratic government, in particular functioned effectively in Azerbaijan. Of course, this was done largely with the intention of establishing buffer states against Bolshevik Russia.

But nevertheless it was a positive development that upset those who were mindlessly agitating in the West for a Greater Armenia and the establishment of a large Christian state among a predominantly Moslem population.

T.P. O’Connor was one of these. And he found himself on a platform in Westminster with a Die-hard terrorist supporting great irredentist objectives involving substantial ethnic cleansing and massacre.

The last word about how T.P.O’Connor met with General Andranik in Westminster in June 1919 should go to British General Thomson:

“Pursuant to our requirement, the Azerbaijani Army was withdrawn from Baku and was deployed in Yelizavetpol to fight against Armenian aggressors, who committed massacres of Muslims under the command of Andranik and Avetisov.” (CAB 45/107, General W.M. Thomson, Narrative of first few days in Baku, November 17th-24th 1918)

https://drpatwalsh.com/2018/07/29/when-t-p-oconnor-met-general-andranik/

© 2009-2025 Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi (AVİM) Tüm Hakları Saklıdır

Henüz Yorum Yapılmamış.

-

THE TALAAT PASHA QUESTION - DRPATWALSH.COM - 13.06.2020

THE TALAAT PASHA QUESTION - DRPATWALSH.COM - 13.06.2020

Pat WALSH 16.06.2020 -

OUR ''GENOCIDAL'' ALLIES (AGAIN) - DRPATWALSH.COM - 21.02.2016

OUR ''GENOCIDAL'' ALLIES (AGAIN) - DRPATWALSH.COM - 21.02.2016

Pat WALSH 21.03.2016 -

THE ILLEGAL SETTLEMENTS OF LEBANESE AND SYRIAN ARMENIANS IN NK - 22.09.2020

THE ILLEGAL SETTLEMENTS OF LEBANESE AND SYRIAN ARMENIANS IN NK - 22.09.2020

Pat WALSH 05.10.2020 -

KHOJALY MASSACRE ANNIVERSARY - DRPATWALSH.COM - 21.02.2022

KHOJALY MASSACRE ANNIVERSARY - DRPATWALSH.COM - 21.02.2022

Pat WALSH 01.03.2022 -

WERE THE ARMENIANS ‘ÜBER-JEWS’? - DRPATWALSH.COM - 26.02.2016

Pat WALSH 21.03.2016

-

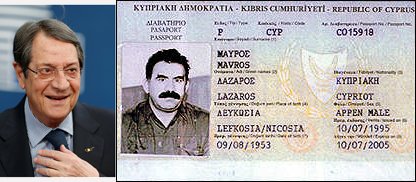

AB, RUMLARIN SİYASİ RÜŞVETİNE DUR DEDİ - ATAATUN.ORG - 25.08.2020

AB, RUMLARIN SİYASİ RÜŞVETİNE DUR DEDİ - ATAATUN.ORG - 25.08.2020

Ata ATUN 31.08.2020 -

PUTIN: THE LEADER THAT FITS RUSSIAN AMBITIONS - HÜRRİYET DAILY NEWS - 23.03.2018

PUTIN: THE LEADER THAT FITS RUSSIAN AMBITIONS - HÜRRİYET DAILY NEWS - 23.03.2018

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 23.03.2018 -

A MORE PERFECT TURKIC UNION? - PROJECT SYNDICATE - 06.12.2021

A MORE PERFECT TURKIC UNION? - PROJECT SYNDICATE - 06.12.2021

Djoomart OTORBAEV 09.12.2021 -

PASHINYAN HEIGHTENS TENSIONS BETWEEN BAKU & YEREVAN OVER “UNITY” SPEECH – CASPIAN NEWS – 07.08.2019

PASHINYAN HEIGHTENS TENSIONS BETWEEN BAKU & YEREVAN OVER “UNITY” SPEECH – CASPIAN NEWS – 07.08.2019

Mushvig MEHDIYEV 08.08.2019 -

SWEDISH EU PRESIDENCY MAKES THEIR FAR-RIGHT A PAN-EUROPEAN THREAT - EU OBSERVER - 13.01.2023

SWEDISH EU PRESIDENCY MAKES THEIR FAR-RIGHT A PAN-EUROPEAN THREAT - EU OBSERVER - 13.01.2023

Malin BJÖRK 16.01.2023